The following is a piece I wrote some five years ago for TGO magazine on the Scandinavian mountains.

The photo shows ski tourers from the Inverness Nordic and Ski Touring Club in the Halingskarvet region of Norway.

The following is a piece I wrote some five years ago for TGO magazine on the Scandinavian mountains.

The photo shows ski tourers from the Inverness Nordic and Ski Touring Club in the Halingskarvet region of Norway.

Scandinavia. The Northland. Trolls, giants, fjords, Vikings, Beowulf, ice, snow, cold. A land of dark harshness and grim bleakness. Maybe. In midwinter. But also wild beauty, unspoiled nature and that special northern light with its subtle play of sun and shadow, a magic light that entices and ensnares, drawing you back again and again. This enchanting land lies just across the North Sea and has some of the finest backpacking and walking terrain in the whole of Europe if not the world. Strangely though this far northern paradise is neglected by British walkers. Go north for glorious walking! The wild lands of Norway, Sweden and Finland are vast, far surpassing in size our own hill country and stretching well north of the Arctic Circle. There are icecaps here, and glaciers, as well as rugged mountains reaching to over 2500 metres in height, vast upland plateaux, huge tracts of boreal forest, crashing waterfalls, wild rivers, myriads of lakes and of course the dramatic and beautiful fjords.

Norway is the wildest of the three countries, mountainous throughout its length. Sweden and Finland are flat, wooded and lake-dotted in the south but have many fine mountains in the north and west. The highest mountains are 2469 metre Galdhøpiggen in Norway, 2117 metre Kebnekaise in Sweden and 1328 metre Halti in Finland. The northern part of all three countries, straddling the Arctic Circle, makes up Lapland, a magical and wondrous place with a real sense of wilderness and remoteness and the beautiful soft light of long northern twilights.

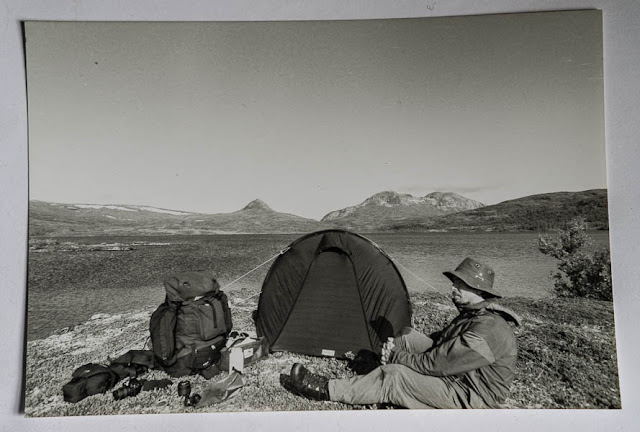

Compared with the British hills, the Alps or the Pyrenees the Scandinavian mountains are quiet and empty, except for the most popular areas at holiday times. It isn’t unusual to walk for days and meet no-one, especially if camping rather than using huts. The walking season isn’t long though, starting after the snow melts in early June and ending in October when the next winter’s snow starts to fall. Winters are long and harsh with little daylight – none at all above the Arctic Circle at midwinter. However late winter and spring – March to early May – are superb times for ski touring with lengthening hours of daylight, warmer weather and fewer storms. Some would argue that the Scandinavian mountains are at their finest at this time of year. In summer the weather is mixed and not dissimilar to that of home, though usually less windy. There is an east-west split, with the former being far drier and sunnier than the latter. In the far north at midsummer there are 24 hours of daylight, which makes it easier to take advantage of the best weather – as long as you don’t mind walking at any hour of the clock.

Much wild land is protected in Scandinavia and there are many national parks – 35 in Finland, 31 in Norway and 26 in Sweden. In Norway these include the Hardangervidda national park, a huge mountain plateau, and Jotunheimen national park– the Home of the Giants. Many days can be spent crossing the high expanse of the Hardangervidda, a rippling upland of rock, moorland and water with a feeling of remoteness, vast space, huge horizons and solitude. In contrast the Jotunheimen is a land of steep rocky, glacier clad mountains packed together above narrow valleys, ideal for those who like bagging summits. There is little that is flat in Jotunheimen and over 200 summits rise above 1900 metres. In Sweden Sarek national park in Lapland is one of the most magnificent wild areas in Europe, a land of alpine summits, glaciers, cliffs and narrow valleys. There are over 200 summits above 1800 metres and 100 glaciers. Sarek is kept wild so there are no huts or waymarks and few bridges, making this a place for the experienced wilderness traveller. Finland’s largest national park is Lemmenjoki in northern Lapland, which is described as “one of Europe’s most extensive uninhabited and roadless backwoods”. The scenery is typical of the wildest parts of Finland and consists of rolling stony hills, forests, lakes and big rivers.

In some respects the Scandinavian mountains are like the Scottish Highlands writ large - very, very large - which isn’t surprising as they were once part of the same range, the great Caledonian Mountain chain, which came into being 400-500 million years ago and then broke up some 65 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean filling the gap left by the torn apart mountains. Today the eroded stumps of the Caledonian Mountains form the Appalachian Mountains in North America, the Scottish Highlands and the Scandinavian mountains. Like the Highlands the Scandinavian landscape we see today was carved by glaciers and then the slow erosion of wind and rain.

Compared with the British hills the Scandinavian mountains have a richer and less despoiled flora and fauna. The mountain flowers are particularly famous and there are around 250 species. These were studied by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus who travelled some 6000km through Lapland in 1732 and went on to invent the scientific system of naming plants and animals. The best time to see these flowers is in early summer straight after snow melt. The Scandinavian mountains are also home to many big mammals that long ago died out in Britain such as moose (called elg or elk), beaver, brown bears, wolverine, lynx and wolves, though the last are very rare. The animals most commonly seen are reindeer, the typical deer of the sub-arctic tundra and forest. Most reindeer are semi-domesticated and owned by the Sami people of Lapland. In southern Norway there are wild reindeer though, which can be seen on the Hardangervidda. Birdlife is prolific, especially in forests and on the coast, and again typical of this northern environment. Special birds that it is always a joy and privilege to see are the white-tailed eagle, gyr falcon and my favourite the long-tailed skua. There are snowy owls too, which I have yet to see.

Although huge and challenging the wild lands of Scandinavia are also accessible and friendly. There are thousands of kilometres of trails and many areas have hut systems. Access is a right, as is wild camping, regardless of land ownership, due to enlightened laws passed in the 1950s. The huts are run by national organisations - Den Norske Turistforening (DNT) in Norway, Svenska Turistföreningen (STF) in Sweden and the Forest and Park Service in Finland. “Huts” range from basic bothy-like shelters through self-catering huts with food supplies, stoves, cooking utensils and bedding to large hotel-like lodges with restaurants and shops. The walking can be as hard or easy as you wish. Scrambles up rocky peaks, long distance walks with camping gear, hut to hut tours on gentle trails are all available. The same equipment suitable for the Scottish Highlands will be fine, perhaps with the addition of a little more warm wear (gloves, hat, extra fleece) as it can be a bit colder.

All three countries have excellent topographic maps, though without as much detail as we are used to from the Ordnance Survey and Harveys. For Norway these are produced by Statens Kartverk. The 1:50,000 series covers the whole country and there are special maps at various scales for many mountain areas with extra information for walkers. Swedish mountain maps are made by Landmateriet at a scale of 1:100,000. In Finland Genimaps cover the mountain areas at various scales from 1:40,000 to 1:100,000 and the National Land Survey maps cover the whole country at 1:50,000. Maps are available from

Stanfords and

The Map Shop .

For backpackers this is near perfect country as you can walk for days, weeks or even months in the mountains without covering the same ground or coming down to cities or developed areas and there are innumerable fine wild camp sites. I spent one summer walking 2200 kilometres south to north through Norway and Sweden, a wonderful experience. Long walks can easily be made by linking paths and there are several long distance routes in the Arctic region, most famously the classic Kungsleden or the King’s Way, a superb trail stretching 450 kilometres through the Swedish mountains from Hemavan to Abisko. The Kungsleden runs through the edge of Sarek and also through Stora Sjöfallet and Abisko national parks as well as passing below Kebnekaise, which can be climbed as a side trip. There are huts along the Kungsleden but there are some sections in the south where distances between them are great and carrying a tent is advisable. The trail is well marked and mostly easy to walk with gentle gradients.

Less well known though equally splendid is Nordkalottleden (Nordkalotrutta), an 800 kilometre trail that runs through all three countries – 380km in Norway, 350km in Sweden and 70km in Finland. Nordkalottleden starts with two paths, one from Sulitjelma in Norway, one from Kvikkjokk in Sweden, that join up at Staloluokta in Sweden. The united trail then runs north to Kautokeino in Norway. En route it passes through Øvre Dividal, Reisa, Abisko and Padjelanta national parks, climbs Halti, the highest mountain in Finland, and visits Treriksröset (the three countries stone), the only place where Norway, Sweden and Finland meet. Nordkalottleden is more of a wilderness walk than Kungsleden as it’s less developed with fewer huts (there are 40 in total, at distances of 10 to 50km apart), less waymarking and some unbridged streams. Not all the huts have food supplies either.

Also in the far north is the Troms Border Trail, which runs for 141 kilometres through northern Norway close to the border with Sweden and Finland and passes through Øvre Dividal national park. One section coincides with part of the Nordkalottleden. Although the route is in Norway the nearest town to the finish is Kilpisjarvi in Finland. This trail is in remote country and the huts along the way don’t have food supplies. It’s ideal for the lover of solitude and unspoilt wilderness.

West of Sarek the Padjelanta Trail runs for 150km through Padjelanta national park, a high tableland mostly above timberline holding some of the biggest lakes in Lapland, from Kvikkjokk north to Akka or Vaisaluokta. The landscape is more open and rolling than Sarek, whose alpine peaks can be seen to the east. There are huts all along the trail though only a few have food supplies.

A little further south, just below the Arctic Circle, and much further east is Finland’s Bear’s Ring Trail, a 95km trail close to the Russian border in Oulanka national park. This runs through old forests, rolling hills and rocky ravines and is well supplied with wood cabins and lean-tos.

Fine though these planned trails are anyone with map reading skills can easily construct their own equally wonderful routes. The first walk I ever did in Scandinavia was a 65km east-west crossing of the Jotunheimen from Gjendesheim to Ovre Ardal via the summits of Glittertind, Galdhopiggen and Fannaraken and the highest waterfall in Norway, 275 metre Vettisfossen. Other great walks are the crossing of the Hardangervidda, which can be done by various routes (I’ve done it three times by different ones), and takes around a week and the walk from the northern Hardangervidda below the Hardangerjøkul ice cap through the rocky Halingskarvet and Fillefjell mountains to Tyin and the southern Jotunheim.

The list of other inspiring and exciting wild areas is long. Sylarna, the southernmost mountains in Sweden. Rondane and Dovre in central Norway. Romsdal with the great walls of the Trolltind in eastern Norway. The spectacular Lofoten islands - mountains rising straight out of the Norwegian Sea. The Lyngen peninsula; arguably the most spectacular mountains in Scandinavia jutting out into the Arctic Ocean. And more, much, much more.

INFORMATION

BOOKS

Climbs, Scrambles and Walks in Romsdal by Tony Howard (Cordee, 2005).

Guide to this spectacular area of Norway.

Hurrungane by James Baxter (Scandinavian Publishing, 2005).

Well-illustrated guide to a beautiful mountain range in western Norway.

Norway South: Rother Walking Guide by Bernhard Pollmann (Rother, 2000).

50 routes from day walks to hut-to-hut tours.

Norway: The Northern Playground by W. Cecil Slingsby (Ripping Yarns, 2003).

Inspiring tales by a pioneering mountaineer, first published in 1904.

Scandinavian Mountains by Peter Lennon (West Col, 1987).

Out of print but worth seeking out used as it’s the only overall guide to the mountain areas of Norway and Sweden.

Walking in Norway by Connie Roos (Cicerone, 2003).

Guide to 20 hut-to-hut walks.

Walks and Scrambles in Norway by Anthony Dyer, John Baddeley and Ian H. Robertson. (Ripping Yarns, 2006).

53 routes including day walks, multi-day backpacks and serious mountaineering expeditions.

HUTS

DNT Norway

STF Sweden